BIOGRAPHY

| Bilton, Nick | American kingpin |

| Cumming, Alan | Baggage |

| Forden, Sara Gay | The house of Gucci |

| Howard, Ron | The boys |

| Mudditt, Jessica | Our home in Myanmar |

| Owens, Mark | Cry of the Kalahari |

| Wassef, Nadia | Chronicles of a Cairo bookseller |

American Kingpin / Nick Bilton

American Kingpin / Nick Bilton

Engrossing account of the rise and fall of Ross Ulbricht, founder of the now-shuttered online drug bazaar the Silk Road. Vanity Fair special correspondent Bilton (Hatching Twitter: A True Story of Money, Power, Friendship, and Betrayal, 2013, etc.) ties his interest in technology to a gritty pursuit tale of the drug underground as it migrated to cyberspace. As the author writes, the Silk Road “could be living proof, Ross fantasized, that legalizing drugs was the best way to stop violence and oppression in the world.” Seemingly another bright, restless millennial, Ulbricht enacted his libertarian beliefs by founding a drug marketplace intended to make purchasing safer and undermine the drug war. Utilizing the “Dark Web” technologies of TOR and bitcoin, Ulbricht’s site opened in 2011 and immediately thrived: “Hundreds of people were now selling drugs on the site, and thousands were buying.” An outlaw subculture quickly developed, drawing in dealers, acolytes, hackers, and scammers; Ulbricht encouraged the notoriety, developing a menacing alter ego, the “Dread Pirate Roberts.” However, he overestimated his ability to avoid law enforcement scrutiny, beginning with low-level mail inspectors suddenly finding numerous identical envelopes of Ecstasy: “Ross had picked a fight with the biggest bully on earth, and the bully was about to punch back.” Chapters generally alternate between Ulbricht’s efforts to stabilize the website while covering his tracks with a self-consciously romantic fugitive lifestyle and the increasingly frantic investigation, which involved competing teams from different agencies (a few of whose members were later convicted of siphoning Ulbricht’s bitcoins and other malfeasance). Ultimately, the Silk Road spun out of Ulbricht’s control, to the point that he was soliciting murders for hire and allowing disguised federal agents to infiltrate the site’s administration. Dramatically arrested by the FBI in a San Francisco library in 2013, he received a life sentence. Bilton writes in a breezy, colloquial style, punctuated by occasional pulpy asides, and he aptly manages the technological arcana of this sprawling story. A fast-paced, readable true-crime tale that frames the likely future of the underground economy. Kirkus Review, May 2017

The house of Gucci / Sara Gay Forden

The house of Gucci / Sara Gay Forden

As the Gucci saga heads to the big screen with a dream-team cast, the opus that inspired it, originally published in 2000, is reissued and updated. Forden begins with a riveting description of the 1995 execution-style shooting of Maurizio Gucci, as witnessed by the doorman of his building. It’s an apt opener given the subtitle. About half of what follows lives up to that billing, and surely it is that half we will see in Ridley Scott’s upcoming film. The other half might be called “A True Story of Boardrooms, Lawyers, Negotiations, and Handbag Manufacturing.” Forden presents the decades of poor business decisions made by the family—as one lawyer put it, “We have to save Gucci from the Guccis!”—in meticulous detail. The author, a former Milan bureau chief for Women’s Wear Daily, does her best to bring the boardroom and banking scenes to life. She also gives a thorough account of the fashion side of the story, from the construction of the iconic bamboo-handle bag to the runway sensations of the “Tom and Dom” era (designer Tom Ford and CEO Domenico De Sole), which included a Gucci G-string. Perhaps the most outrageous of the many larger-than-life characters is Patrizia Reggiani (played by Lady Gaga in the film), a shameless gold digger who announced she would rather “weep in a Rolls-Royce than be happy on a bicycle” and blithely ordered the murder of her husband when their interests diverged. As her own lawyer put it, “This story makes a Greek tragedy look like a children’s story.” According to Forden, “the trial spotlighted the passionate, excessive lives of Maurizio and Patrizia in stark contrast to the gray squalor in which Pina and her three accomplices lived. And like the O.J. Simpson trial, which underscored divisive racial attitudes in American society, the Gucci trial highlighted the chasm separating wealthy from poor in Italy.” An epic story told in epic detail. Kirkus Review October 2021

The boys / Ron Howard

The boys / Ron Howard

Brotherly coming-of-age reflections from a storied life in show business. The glowing foreword, by Bryce Dallas Howard, sets the tone for this forthright memoir from her father, Ron, and his younger brother, Clint. Both were primed for the entertainment industry from a young age by beloved Oklahoman parents Rance Howard and Jean Speegle, self-proclaimed “sophisticated hicks” who relocated to New York City in their youth and embarked on a “rich and strange” journey to realize their own showbiz aspirations. Written in alternating segments, the brothers offer crisp, mostly interesting insights into their separate trajectories into the entertainment business. Ron writes about being diligently prepped for screen tests near his fourth birthday by his father, who taught both sons to “understand a scene in an emotional language,” while Clint notes that both were spared becoming “Hollywood casualties” due to the values their parents instilled in them. The authors chronicle the ups and downs of lifetimes in acting—early on, Ron in the Andy Griffith Show and Happy Days, and Clint in an episode of Star Trek before Gentle Ben—as well as belonging to a household fully ensconced in the entertainment industry. Despite a competitive edge between them—which still remains, as Clint acts in many of Ron’s directorial productions—as they struggled up the Hollywood ladder, their familial bond remained strong. Both brothers add some behind-the-scenes snippets; for example, Ron discusses his newfound adulthood appreciation for Andy Griffith while he shot isolated scenes for Return to Mayberry. For the most part, the binary autobiographical approach works, with the alternating commentaries and interpreted memories from each author offering divergent yet complementary perspectives. A treat for movie and TV buffs, this dual memoir is wholesome and satisfying. Fans of the Howards will revel in the details of their young ascents into the Hollywood spotlight. Kirkus Review October 2021

Return to top

GENERAL FICTION

| Allsopp, Kimberley | Love and other puzzles |

| Barrett, Shirley | Rush oh! |

| Bonner, Sarah | Her perfect twin |

| D’Andrea, Luca | The wanderer |

| Day, Elizabeth | Magpie |

| Jeffers, Honoree Fanonne | The love songs of W.E.B. Du Bois |

| Keneally, Thomas | Corporal Hitler’s pistol |

| Le Tellier, Herve | The anomaly |

| Maher, Kerri | The Paris bookseller |

| Natsukawa, Sosuke | The cat who saved books |

| North, Lauren | Safe at home |

| Percy, Tom | The curate’s egg |

| Phelps, James | The inside man |

| Roy, Jacqueline | The Gosling Girl |

| Steel, Danielle | Invisible |

| Trant, Michael | Wild Dogs |

Rush oh! / Shirley Barrett

Rush oh! / Shirley Barrett

While Australian screenwriter Barrett bases her first novel on the story of real-life whaler George “Fearless” Davidson, George’s prickly yet endearing daughter Mary is the star. Thirty years after the fact, Mary Davidson sets out to write about the season of 1908, which she sees as a turning point in New South Wales’ whaling business—the beginning of the decline in the number of whales as well in demand for whale oil, as kerosene became widely available, and for whalebone, as women stopped wearing corsets. In 1908, Mary is 19 years old and running the household, which includes her three younger sisters and two brothers, for her widowed father. Her portrait of family life is drolly tart and unsentimental. Actually, so is her portrait of herself, until the day ex–Methodist minister John Beck shows up to work for Mary’s father despite a complete lack of experience as a whaler. Mary is never able to piece together Beck’s whole back story, and neither is the reader; maintaining the mystery of his past and his motives is a daring choice by the author, teetering as it does between provocative and irksome. Despite Mary’s awkward manners, she and John begin a flirtation that threatens to become something deeper. Meanwhile, Mary’s pretty and charming 16-year-old sister, Louisa, whom Mary claims to disdain for her frivolity, wards off a variety of suitors. But Louisa proves more complicated than Mary realized when she makes a shocking decision that throws the family into chaos. Mary’s narrative reflects her just-the-facts-ma’am personality, and she describes the fundamentals of whaling in more depth than will interest any but the most die-hard aficionado (although the relationship between the whalers and the local killer whales, with names like Tom and Jackson, is fascinating, given what scientists have since discovered about their intelligence). But despite herself, Mary’s emotions slip between the facts, particularly in small, often bittersweet asides about what’s happened to various Davidsons in the years since 1908. Yes, there’s a lot of whaling talk, but with a narrator reminiscent of Jo March, the sensibility here is more akin to Little Women than Moby-Dick. Kirkus Review March 2016

The anomaly / Hervé Le Tellier

The anomaly / Hervé Le Tellier

A mystifying phenomenon sends shock waves through the world of an alternate 2021. The opening chapter presents a detailed portrait of a professional assassin called Blake, a man described as “extremely meticulous, cautious, and imaginative.” The same adjectives could be applied to author Le Tellier: Trained as a mathematician and a scientific journalist, he uses these first pages to prime the reader for his methodically crafted story. The action then abruptly jumps to Victor Miesel, a disillusioned author and translator who becomes “mired in a horrible impression of unreality” after a turbulent flight. Over the following weeks, Miesel feverishly writes a new book called The anomaly, sends it to his editor, and kills himself. Then, snap, a new chapter begins, introducing a film editor named Lucie, who, along with every subsequently introduced character (eleven, altogether), is inexplicably requisitioned by the authorities.The connection between these people soon becomes clear: They were all passengers on the same turbulent flight. What exactly happened on this airplane? Le Tellier withholds the details for long enough that revealing the mystery here would spoil the entrancing quality of the book. Hunter’s brilliant translation from the French—her fifth collaboration with Le Tellier—transforms Le Tellier’s distinct French voice into a distinct English one. More importantly, Hunter captures the playful exhilaration with which Le Tellier marries his audacious plot to a deep concern for existentialist philosophy. Excerpts from Miesel’s The anomaly appear in epigraphs for each new section, including: “There is something admirable that always surpasses knowledge, intelligence, and even genius, and that is incomprehension.” Humorous, captivating, thoughtful—existentialism has never been so thrilling. Kirkus Review, November 2021

The Cat who saved books / Sosuke Natsukawa

The Cat who saved books / Sosuke Natsukawa

A young Japanese bookseller sets out to rescue books in peril—with the help of a most unusual feline. After the death of his beloved guardian and grandfather, high school student Rintaro Natsuki drifts into running his grandfather’s rare bookshop while waiting to be sent to live with an aunt he doesn’t know. Rintaro is a hikikomari—socially withdrawn and isolated from most activities—and finds comfort and meaning in the books so precious to his plainspoken and well-meaning grandfather. His quiet, solitary life is disrupted when, in a bolt of magical realism, a talking tabby cat named Tiger enlists his help in rescuing “books that have been imprisoned.” Some of the victimized books are locked away from readers by collectors, others are mutilated by abridgment and summarization, and more are treated as commodities by publishing conglomerates. Rintaro undertakes the challenges assisted by the saucy cat few humans can see, and his quests resemble the tests posed to heroes in myth, legend, and video game. His growing awareness of the attentions of persistently positive schoolmate Sayo lends the tale a gentle wholesomeness. Rescuing the story from sappiness are references to the classic books on the store’s shelves, mostly from the Western canon, that have formed Rintaro’s belief system. Lovers of traditional literature and books themselves will find validation in the lessons Rintaro learns (and teaches), while the story’s structure and fanciful nature may hold appeal for a young adult audience more familiar with the conventions of gaming. Tiger gets the best lines of dialogue but…why not? Cats, books, young love, and adventure: catnip for a variety of readers! Kirkus Review, December 2021

Return to top

HISTORICAL FICTION

| Hopkins, Ben | CATHEDRAL |

| Pook, Lizzie | Moonlight and the pearler’s daughter |

| Thorp, J R. | Learwife |

| Tokarczuk, Olga | The books of Jacob |

Cathedral / Ben Hopkins

Cathedral / Ben Hopkins

This first novel by screenwriter Hopkins imagines a paean to the glory of God arising from the unholy muck of the Middle Ages. By the year 1229, a lofty Cathedral—a bishop’s vanity project, always capitalized—is already in the works in Hagenburg, Germany. The Bishop’s treasurer is not enamored of the idea, opining that “a constant river of silver and gold flows into that damned hole, providing the wages of the idle, and paying quarrymen, foresters and glaziers for their so-called labour.” The bishop has just “passed into Glory,” the Lord Treasurer is abroad, the pope is dead, infidel hordes besiege Jerusalem, and “all is in turmoil and flux.” No wonder the Cathedral takes so long to build. Meanwhile, young Rettich Schäffer is an apprentice stonecutter working on the Cathedral, wanting to buy his freedom from the bishop, so he borrows from a Jewish moneylender. The stories of Christians and Jews intertwine over the decades, with piety and decency largely absent from center stage. Surrounding the rising edifice in Hagenburg are degradations of every kind—“the siren calls of Temptation, Debauchery and Vice” and “the Magical World of the Goyyim. Sodom without cataclysm.” Hypocrisy abounds, as when Father Arnold chants over the bodies of dead bandits, because “God listens to what he says….The priest gets an extra sixpence for every Last Rite he gives. He was probably praying for a massacre.” Jews like Yudl ben Yitzhak Rosheimer privately regard the Cathedral as “the Abomination.” To him it is “just a pile of stones and vain idols, an excrescence of the sinful earth.” Well, it’s either that or “the finest Cathedral in the German Lands.” Across the decades, no one character dominates this story of ambition, vanity, and power. In the midst of a plague, a mother and child find cold comfort within the completed empty church as “the Witch of Winter rode the wind.” A thoroughly engrossing, beautifully told look at human frailty. Kirkus Review, January 2021

Moonlight and the Pearler’s Daughter by Lizzie Pook

Moonlight and the Pearler’s Daughter by Lizzie Pook

This is a charming novel that starts in 1886, when 10-year-old Eliza Brightwell arrives with her family at the tropically hot and terrifyingly remote Bannin Bay (based on the area of Broome, Western Australia). Here her beloved father hopes to make his fortune from the mother-of-pearl shell that is in demand. Ten years later, things have not quite gone to plan, but the family owns a lugger, and her father, Charles, is the Bay’s most successful pearler. Eliza always goes down to meet the returning ship. One day, after a spell out at sea, her father simply doesn’t come back. There is talk of mutiny and murder, but Lizzie knows that her father’s crew is devoted to him, and that he is a fair man. She attempts to get the authorities in town to investigate, refusing to believe that her father has just disappeared at sea, but the town is rife with corruption and prejudice, and they believe the matter is an open-and-shut case. Eliza remembers that her father always said that if she was lost he would come and find her, and she decides that this is just exactly what she must do for him. This novel is similar to many others set in the area of Broome and, although I was hoping for a bit more, the author does a fine job of painting colonialism in North-Western Australia and the injustices against the local Aboriginal people, providing a real sense of place and time. Eliza is a feisty heroine indeed, and her adventures are certainly entertaining. Good Reading Magazine, March 2022.

The Books of Jacob / Olga Tokarczuk

The Books of Jacob / Olga Tokarczuk

A charismatic figure traverses Europe, followers in tow. The latest novel by the Polish Nobel Prize winner to appear in English is a behemoth, both in size and subject matter: At nearly 1,000 pages, the book tackles the mysteries of heresy and faith, organized religion and splinter sects, 18th-century Polish and Lithuanian history, and some of the finer points of cabalist and Hasidic theology. At its center is the historical figure Jacob Frank, who, in the mid-1750s, was believed to be the Messiah by a segment of Jews in what is now Ukraine. Jacob preached that the end times had come and that morality, as embodied by the Ten Commandments, had been turned on its head. He led his followers to convert first to Islam and then, later, to Christianity. He himself was accused of heresy by all three major groups. Tokarczuk’s account is made up of short sections that alternate among various points of view. These include some of Jacob’s followers, a bishop with a gambling problem, a noblewoman who self-interestedly supports the “Contra-Talmudists’ ” attempt to convert to Christianity, and Jacob’s grandmother Yente, who is neither dead nor entirely alive, a state that allows her consciousness to roam widely, observing the novel’s action. Gritty details about the realities of daily life at the time alternate with dense passages in which Jacob’s followers argue about theology. “The struggle is about leaving behind that point where we divide everything into evil and good,” one says, “light and darkness, getting rid of all those foolish divisions and from there starting a new order all over again.” The book (which has been beautifully translated into English by Croft) has been widely hailed as Tokarczuk’s magnum opus, and it will likely take years, if not decades, to begin to unravel its rich complexities. A massive achievement that will intrigue and baffle readers for years to come. Kirkus Review February 2022

Return to top

MYSTERY

| Barclay, Linwood | Take Your Breath Away |

| Bowen, Rhys | God rest ye, royal gentlemen |

| Bryndza, Robert | Darkness falls |

| Carroll, Ber | You had it coming |

| Finch, Charles | An extravagant death |

| Glenconner, Anne | A haunting at Holkham |

| Griffiths, Elly | The locked room |

| Gudenkauf, Heather | The Overnight Guest |

| Hannah, Sophie | The couple at the table |

| Heath, Jack | Hideout |

| Levitt, Michael | The Gallerist |

| Mckenzie, Dinuka | The Torrent |

| Parrish, P. J. | The damage done |

| Patterson, James | Steal |

| Robb, J. D | Abandoned in death |

| Rosenfeldt, Hans | Cry wolf |

| RUTKOSKI, MARIE | REAL EASY |

| Tudor, C.J. | The burning girls |

| Underdown, Beth | The key in the lock |

| Willberg, T. A. | Marion Lane and the midnight murder |

| Young, Erin | The fields |

God Rest Ye, Royal Gentlemen / Rhys Bowen

God Rest Ye, Royal Gentlemen / Rhys Bowen

Christmas 1935 finds murder stalking the British royal family. Lady Georgiana Rannoch is settling into married life with dashing Darcy O’Mara, who for once isn’t off on some secret government mission. When the house party she’s planned falls apart because almost no one she’s invited can come, she accepts an invitation of her own. Darcy’s eccentric aunt Ermintrude asks the newlyweds to Wymondham Hall, on the edge of the royal Sandringham estate, and hints that Queen Mary especially wants Georgiana to come. There are enough rooms on offer to allow the inclusion of Georgie’s brother, Binky, the Duke of Rannoch, his annoying wife, Fig, their children, and Georgie’s mother, the dowager Duchess, who’s suddenly arrived from Germany. Georgie even brings along Queenie, her cook, who has a reputation for causing problems. The biggest surprise is the arrival of Wallis Simpson, whom Georgie’s cousin David, the Prince of Wales, wants close by his side while he visits his ailing father. The British press has been keeping Mrs. Simpson, who’s about to divorce her husband, a secret from the public, but the scandal she’s caused is well known among the aristocracy. David is almost shot during a hunt; Mrs. Simpson is knocked out; and Georgie’s ride with the prince’s friend results in his death. Are these all accidents or cleverly concealed murder attempts? Queen Mary asks Georgie, who has a track record of successful sleuthing, to discover the truth. Britain teeters on the brink of scandal and war in this charming combination of history and mystery. Kirkus Review October 2021

Abandoned in Death / J. D. Robb

Abandoned in Death / J. D. Robb

June 2061 is a perilous time for women in a downtown Manhattan neighborhood who happen to resemble a violent kidnapper’s mother. The killer doesn’t seem to be trying to hide anything except his own identity. Ten days after snatching bartender Lauren Elder from the street as she walked home, he leaves her body, carefully dressed and made up, with even the gash in her throat meticulously stitched up and beribboned, where it’s sure to be found quickly, along with the chilling label “bad mommy.” When Lt. Eve Dallas and Detective Delia Peabody realize that Anna Hobe, a server at a nearby karaoke bar who disappeared a week ago under similar circumstances, was probably another victim of the same perp, the clock begins ticking down even before they learn that assistant marketing manager Mary Kate Covino has gone missing as well. Dallas, Peabody, and the helpers who’ve made Robb’s long-lived franchise even more distinctive than its futuristic setting race to find the women or identify their kidnapper before he reverts once again to the 5-year-old abandoned by his mother many years ago. The emphasis this time is on investigative procedure, forensics (beginning with the Party Girl perfume and the Toot Sweet moisturizer the murderer uses on the corpses of his victims), and the broader danger women in every generation face from men who just can’t grow up. A rarity: a police procedural more deeply invested in the victims than either the killer or the police. Kirkus Review, February 2022

The Burning Girls / C. J. Tudor

The Burning Girls / C. J. Tudor

A fresh start for a vicar and her daughter proves to be anything but. When vicar Jack Brooks’ boss asks her to leave St. Anne’s in Nottingham for a more rural placement in the small Sussex village of Chapel Croft, it’s more an order than a favor. She’ll serve as interim vicar until a suitable replacement for the former vicar can be found. Jack’s 15-year-old daughter, Flo, isn’t thrilled to leave the city, but she knows that her mother could use some distance from a horrific tragedy at St. Anne’s that Jack feels largely responsible for. Soon after they arrive at Chapel Croft, however, they learn that their new village has more than its share of weirdness and tragedy. The vicar that preceded Jack allegedly hung himself in the chapel; Merry and Joy, two teen girls, disappeared without a trace 30 years ago; and the village is known for the Burning Girls, aka the Sussex Martyrs, who were burned at the stake in the 16th century. Additionally, Jack keeps finding strange twig dolls on the church grounds and disturbing accounts of exorcisms in her cottage’s cellar. Meanwhile, Flo glimpses strange figures in the graveyard and befriends Lucas Wrigley, a troubled boy with a shady past. Then there are the bodies that keep turning up while dark secrets emerge about a local (and very powerful) family. The author steadily cranks up the scares and the suspense while smoothly toggling between multiple narratives, including one that indicates Jack’s past may be about to catch up with her. Jack is immensely appealing: She curses and smokes, and her faith, which she explores throughout, is complicated. Luckily, Jack and Flo share a strong bond, one they’ll need in order to face what’s coming, and readers will savor the final, breathless twists. Top-notch and deliciously creepy storytelling. Kirkus Review, February 2021

Marion Lane and the midnight murder / T.A. Willberg

Marion Lane and the midnight murder / T.A. Willberg

Set in 1958 London, Willberg’s assured debut, which is equal parts mystery and whimsical fantasy, plunges Marion Lane, a first-year apprentice at the shadow spy agency Miss Brickett’s Investigations and Inquiries, into the case of Michelle White, a much-loathed filing assistant, who was stabbed to death with one of the agency’s futuristic spy gadgets. The nature of the murder weapon leads Marion to believe that Michelle had incriminating information on her murderer. But when Marion’s mentor and protector, Frank Stone, comes under suspicion, Marion has to muster her investigative skills and those of her fellow apprentices to prove Frank’s innocence before Frank is sent to live out his days in the Holding Chambers, a forbidding prison for inquirers who have gone rogue. Willberg does an admirable job of world building, in particular Miss Brickett’s, which exists in an underground labyrinth far beneath the streets of London. Two distinctive supporting characters, best friend Bill Hobb and handsome American love interest Kenny Hugo, compensate for others who fail to pop. Readers will be curious to see where Marion goes next. Publishers Weekly, September 2020

Return to top

NON FICTION

| Hayes, Bill | Sweat |

| Roberts, Alice | Ancestors |

| Harper, Melissa | Symbols of Australia |

Sweat: A History of Exercise / Bill Hayes

Sweat: A History of Exercise / Bill Hayes

Obsessed by both working out and its history, Hayes writes a book that combines them. A successful freelance author, journalist, photographer, and editor, the author is not shy about describing his lifetime preoccupation with running, gym workouts, and aerobics, with diversions into boxing, swimming, and biking. After recording exercises favored by such towering historical figures as Einstein (“didn’t look like a strapping athlete, but he didn’t look like he never exercised either”), Tolstoy, and Kafka, Hayes delves more deeply into the subject. He hit the jackpot in the rare book room of the New York Academy of Medicine, discovering a huge, brilliantly illustrated edition of “De arte gymnastica (The Art of Gymnastics), dated 1573. The author was Girolamo Mercuriale, a name previously unknown to me.” As Hayes learned, the book was an effort to revive Greek and Roman love of exercise. Reappearing throughout this book, De arte provides much of the inspiration for Hayes’ exploration. “In ancient Greece and in the early Roman Empire,” he writes, “there was at least one gymnasium in every town. The gymnasium was as much a part of culture and society as a theater and marketplace.” Authorities from Hippocrates to Plato extolled exercise, a point of view snuffed out by the rise of Christianity, when “Cathedrals replaced gymnasiums as sacred sites; it was the holy spirit—the soul—that was now to be glorified, not the body.” By the 16th century, Renaissance humanism was reviving the former view. This book is largely a record of the author’s travels across the world, where he visited libraries and interviewed scholars and scientists or simply people he encountered along the way. He recounts exercise history and how he continued his daily workouts despite often primitive local facilities, and he interjects episodes from his past that are more or less related to the active life. Fittingly, he ends at the Olympia site in Greece. An entertaining hodgepodge of autobiography, travelogue, and history. Kirkus Review, January 2022

Return to top

POETRY

| Headley, Maria Dahvana | Beowulf |

Beowulf / Maria Dahvana Headley

Beowulf / Maria Dahvana Headley

An iconic work of early English literature comes in for up-to-the-minute treatment. In her novel The Mere Wife (2018), Headley imagined Grendel’s mother as a PTSD–haunted Iraq War veteran guarding her son from the encroachment of suburban civilization on their wilderness home. Telling that tale, she recounts in the introduction here, put her closely in touch with the original and with a woman who “had a ferocious look and seemed to give precisely zero fucks.” From the very opening of the poem—“Bro!” in the place of the sturdy Saxon exhortation “Hwaet”—you know this isn’t your grandpappy’s version of Beowulf. Headley continues, putting her own spin on the hemistiches and internal rhymes of the original: “Tell me we still know how to talk about kings! In the old days, / everyone knew what men were: brave, bold, glory-bound. Only / stories now, but I’ll sound the Spear-Danes’ song, hoarded for hungry times.” Grendel, she has it, was a “woe-walker, / unlucky, fucked by Fate.” The language may keep Headley’s version from high school curricula, but the sentiment is exactly right: Grendel is an outcast and monster through no fault of his own while the men who array themselves against him are concerned with attaining fame and keeping the reputation of being good for eternity while having a nice flagon of mead at the end of a day of hacking away. Headley’s language and pacing keep perfect track with the events she describes, as when a fire-breathing dragon visits the warriors’ hall: “Soon Beowulf received a blistering missive. / His own hall, his heart-home, had combusted. / He’d been ghost-throned by the skyborn gold-holder.” “Ghost-throned” is a wonderful neologism, and if phrases like “Everybody’s gotta learn sometime” and “His guys tried” seem a touch too contemporary, they give the 3,182-line text immediacy without surrendering a bit of its grand poetry. Some purists may object to the small liberties Headley has taken with the text, but her version is altogether brilliant. Kirkus Review, August 2020

Return to top

SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY

| Aaronovitch, Ben | What Abigail did that summer |

| Koontz, Dean R. | Elsewhere |

| Muir, Tamsyn | Harrow the Ninth |

| Wells, Martha | All systems red |

Elsewhere / Dean Koontz

Elsewhere / Dean Koontz

California man Jeffy Coltrane and his 11-year-old daughter, Amity, discover the wonders and horrors of multiverse travel after an inventor entrusts them with a special device. The inventor, on the run from dark government forces, instructs Coltrane to put this $76 billion “key to everything” into safekeeping and never use it. But when Amity’s pet mouse strolls across its controls, the device activates, whisking father and daughter—and mouse—off to an alternate Earth. Danger greets them in the form of a nasty creature that is half boy and half chimp, and there are other threats. But Amity is in no rush to return to normalcy after Googling her long-missing mother and determining she is alive and well on Earth 1.13. However, re-connecting with Mom, who walked out on her family seven years ago, saying she felt “empty,” proves problematic: In this parallel world, Jeffy and Amity were both run over by a car—seven years ago. For all the other scary things there are across the multiverse, including genocidal robots marching up the Pacific Coast Highway, none is more frightening than the neo-fascist enforcers now operating back home on “Earth Prime.” As heavy-handed as Koontz is in nailing down this timely theme, it’s disappointing to see him pull back from its broader implications and invest his villainy in a rather predictable sociopathic bad guy who will do anything to lay his hands on the special device. And it is not always easy to keep all the multiple Earths and versions of people straight. But otherwise, this is a colorful, imaginative spin into SF by the prolific, wide-ranging writer. A lively, offbeat novel. Kirkus Review, October 2020

Harrow the Ninth / Tamsyn Muir

Harrow the Ninth / Tamsyn Muir

Quirky space opera, dark fantasy, Gothic novel, and unreliable-narrator thriller combine in unusual and unpredictable ways in the second of a series. Harrowhark the First, newly created Lyctor of the Emperor—a near-immortal councilor and warrior—is in some difficulties. The young necromancer is having serious trouble integrating the soul of her sacrificed cavalier, a necessary step in assuming her full powers and ensuring her body will fight when her soul is immersed in the undead realm of the River. Perhaps this trouble stems from her mistaken belief that her dead cavalier was cowardly bad poet Ortus Nigenad; readers of the previous volume, Gideon the Ninth (2019), know that Ortus died before the Lyctor challenge began; Harrow’s true cavalier primary was the crude, defiant, and appealing young woman known as Gideon Nav. Harrow’s rewritten memories of a past that never happened as well as her conviction that she’s insane makes it nearly impossible for her to fully prepare for a hopeless battle with a planet’s vengeful soul—or to determine what’s real from moment to moment. Harrow is nowhere near as fun a protagonist as snarky, passionate Gideon, and we soon realize that her troubles are mostly self-inflicted. Although she remains sympathetic, Harrow wanders through most of the book confused, sad, desperate, and repressed except for a secret and kind of creepy passion for the Body, a beautiful, feminine-appearing preserved corpse she glimpsed in the taboo and supposedly inaccessible Locked Tomb at her home, and whose ghostly presence seems to follow her everywhere. It’s somewhat grim going until the final fifth of the book, when the story gathers itself with thrilling speed, delivering exciting action sequences and explosive revelations. A slow-gathering hallucinatory adventure that eventually delivers a great payoff. Kirkus Review, August 2020

All systems red / Martha Wells

All systems red / Martha Wells

SecUnit, aka Murderbot, is a semiorganic corporate profit center, genderless and constructed of cheap parts to perform contract bodyguard services for clients who mostly don’t want them. SecUnit can choose its attitude because it has hacked its governor (a hat-tip to Susan R. Matthews), blocking the functions that would punish it for anything but robotic obedience. Disgusted by humans and secretly addicted to a video serial called Sanctuary Moon, SecUnit is simply enduring another assignment until something completely outside of its data parameters tries to kill its humans. Nebula finalist Wells (Edge of Worlds) gives depth to a rousing but basically familiar action plot by turning it into the vehicle by which SecUnit engages with its own rigorously denied humanity. The creepy panopticon of SecUnit’s multiple interfaces allows a hybrid first-person/omniscient perspective that contextualizes its experience without ever giving center stage to the humans. Publishers Weekly, March 2017

Return to top

New additions to eBooks at SMSA

EBOOKS

| Biography | Qu, Anna | Made in China |

| General novels | Brugman, Emily | The Islands |

| General novels | Caro, Jane | The mother |

| General novels | Cooper, Catherine | The Chateau |

| General novels | Jaffe, Meredith | The tricky art of forgiveness |

| General novels | Jonas, Julia | Vladimir |

| General novels | Lowe, Fiona | A family of strangers |

| General novels | Scott, Caroline | The visitors |

| Mystery | Hendricks, Greer | The golden couple |

| Mystery | Hendy, Hannah | The dinner lady detectives |

| Mystery | Lloyd, Ellery | The club |

| Mystery | McEwan, Lynne | In dark water |

Made in China / Anna Qu

Made in China / Anna Qu

A grim yet gripping memoir of an unhappy, nearly loveless childhood and the author’s determined escape to a better adulthood. Born in Wenzhou, China, Qu remained with her grandparents after her father died—whether of illness or in an auto accident, she was never sure—and her mother moved to New York. There, her mother “worked hard, caught the eye of the owner of the sweatshop she worked in, remarried, and had two kids. Not only had she succeeded in making her American dream come true, she had also managed to bring her 7-year-old daughter with her. It was an achievement worth celebrating.” When she moved in with her new family, the parents showered her half siblings with attention, food, and gifts—but not the author. Still a child, she was put to work in that sweatshop, toiling under the eye of her stepfather for 40 or 50 hours per week; at home, she was banished to the basement. Finally, her mother sent her back to China only to allow her to return to live not as the “outsider” of before but now as a clear “intruder.” Qu describes her mother with steely words: “She wore a fitted red suit with kitten heels,” for instance, “her hair pulled back from her face in a neat way that made her opinion a fact.” Eventually, the author filed a complaint with child protective services and was met with indifference. “The system I turned to is ineffective, neglectful, and careless,” she writes. “I was wrong to call them, wrong to think they stood for justice and the safety of children, wrong to be naïve, wrong to be so idealistic.” Later, Qu left for college, working diligently in both school and as a restaurant server and retail salesperson, earning grudging respect—but still not love—from her mother. The book is well written and sometimes brilliantly insightful, but it’s also saturated with seething resentment that, while thoroughly understandable, may turn some readers away. A simultaneously powerful and depressing latter-day Dickensian story sure to elicit sympathy from readers. Kirkus Review, August 2021

The golden couple / Greer Hendricks

The golden couple / Greer Hendricks

Risk taking has helped make Avery Chambers, the protagonist of this suspenseful if not always credible thriller from bestsellers Hendricks and Pekkanen, the hottest mental health professional in Washington, D.C., but her maverick approach, at times incorporating techniques more typically employed by PIs (like tailing patients to check up on them), does have its dangers. Already on edge after making a whistleblower call to the FDA concerning a pharmaceutical company’s malfeasance, the recent widow starts to experience unsettling events, like what looks to be a professional break-in of her home, around the time she begins treating lawyer Matthew Bishop and his wife, boutique owner Marissa. Avery senses there’s much more going on with this power couple than their stated infidelity issue—but can even someone as resourceful as Avery get to the bottom of a relationship stretching back to the pair’s teens, and to the murder of Marissa’s best friend back then, in time to avert disaster? The authors keep the pages turning and the book represents a return toward the high standard of their early nail-biters. Publishers Weekly, December 2021

Vladimir / Julia Jones

Vladimir / Julia Jones

Playwright Jonas debuts with a mordantly funny post-#MeToo campus story about a 50-something woman unhinged by desire for a younger man. The unnamed narrator, a tenured English professor at a small upstate New York liberal arts college, starts the fall semester embroiled in scandal. The scandal is not hers (at least not at first)—her husband, John, also a professor in the department, has been placed on leave pending the results of a hearing after being accused of sexual predation by a host of young women, many of them former students. Denounced by both her colleagues and her adult daughter for her complicity in John’s behavior, the narrator retreats into obsessive sexual fantasies about a new young colleague, Vladimir. She also yearns to recapture the physical allure of her youth and revive her own stagnant writing, and by the end, her behavior turns monstrous. Vain, narcissistic, and seemingly oblivious to the absurdity of her actions, the narrator can nevertheless pluck at readers’ sympathies, especially in the generous and thoughtful ways she helps her daughter during her own personal crisis. The author generously studs the narrative with clever literary allusions (the narrator describes her mind in contrast to Edna St. Vincent Millay’s: “more like a chaotic battle scene than the unfurling of insight”), and surprisingly upends assumptions about gender, power, and shame. Jonas is off to a strong start. Publishers Weekly, November 2021

Return to top

AUDIOBOOKS

| Biography | Cheung, Karen | The impossible city |

| General novels | Coble, Collen | A stranger’s game |

| General novels | Probst, Jennifer | The secret love letters of Olivia Moretti |

| Mystery | Clifford, Aoiffe | When we fall |

| Mystery | Ellis, Joy | Fear on the Fens |

| Mystery | Miller, Carol | The fool dies last |

| Mystery | Miscellaneous | Midnight hour |

| Mystery | Dark, Rylie | Only murder |

| Mystery | Thompson, Victoria | Murder on Mulberry Bend |

| Mystery | Viskic, Emma | Those who perish |

The impossible city / Karen Cheung

The impossible city / Karen Cheung

An intimate look at Hong Kong by an “ambivalent” native who never appreciated it until the incremental seizure of freedoms by mainland China. Cheung is one of the few in her cohort trying to stay in Hong Kong and make a living despite the crackdown, and she has dedicated herself to getting to know her city as its character, she fears, is slipping away. The colonial handover from Britain occurred on July 1, 1997, when the author was just 4 years old. “At Tiananmen Square, where less than a decade ago students were killed asking for democracy,” she writes, “Beijingers are waving little handheld flags with the Hong Kong bauhinia flower stamped onto it, celebrating our return.” Cheung’s parents separated, and her mother went to Singapore with her younger brother; the author lived in Hong Kong with her critical, authoritative father but was largely raised by her paternal grandmother, who she felt was the only one who loved her. She could not wait to leave home at age 18. Her generation felt they had a grace period of decades until China actually took over—“one country, two systems model to guarantee the city’s way of life”—but by 2014, China was cracking down on Hong Kong’s election autonomy, actions that led to the emergence of the Umbrella Movement. At this point, Cheung, now a journalist, grew politicized, and she also suffered debilitating depression, which her family did not understand and that further alienated her from them. In June 2020, a national security law was passed, which “marked the turning point for a total crackdown that soon infiltrated all aspects of life.” In a book that should appeal to young protesters everywhere, the author eloquently demonstrates how “it takes work not to simply pass through a place but instead to become part of it.” Hong Kong is in dire straits, and Cheung brings us to the front lines to offer a clearer understanding of the circumstances. A powerful memoir of love and anguish in a cold financial capital with an underbelly of vibrant, freedom-loving youth. Kirkus Review, February 2022

Midnight hour / Miscellaneous

Midnight hour / Miscellaneous

An exciting anthology of 20 crime and suspense tales by and about people of color. Vandiver brings together a diverse group of short stories that chill and thrill in their exploration of the many human passions that lead to crime. Tracy Clark tells the tale of a young punk looking for easy money who makes the fatal mistake of choosing the wrong victim. David Heska Wanbli Weiden explores the theft of a book covered in the skin of a Native American that turns out to be much more than a theft for hire. Editor Vandiver’s tale of murder has a surprise you won’t see coming. Callie Browning’s story of hate and karma is set on tropical Barbados. Richie Narvaez’s account of blackmail and revenge in Puerto Rico has plenty of odd twists. A district nurse and a parrot help solve a convoluted case of murder during a robbery in Frankie Y. Bailey’s quick read. E.A. Aymar surveys the choices available to a man down on his luck. Jennifer Chow follows two old high school friends whose decision to meet in an escape room has unexpected consequences, and magic and a séance drive Gigi Pandian’s story of a clever escape from an abusive husband. This eclectic collection will appeal to mystery readers. An excellent collection of stories told from many different viewpoints. Kirkus Review, November 2021

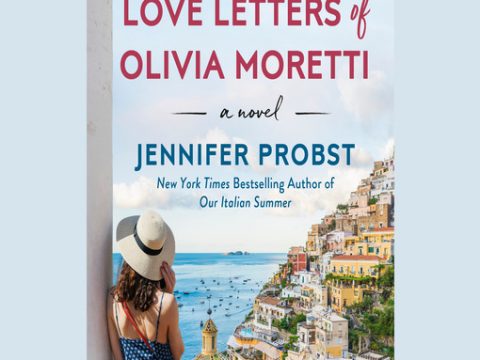

The secret love letters of Olivia Moretti / Jennifer Probst

The secret love letters of Olivia Moretti / Jennifer Probst

Probst’s engaging if sometimes clunky latest (after Our Italian Summer) follows three American sisters as they visit Positano, Italy, to find answers to mysteries unearthed following their mother’s death. Former ballerina Pris gave up her career for love but has grown apart from her busy lawyer husband, Garrett. Her younger sister Dev, a workaholic NYU professor, judges their youngest sister, Bailey, for hooking up with guys and never committing. After their mother, Olivia, dies, the siblings find love letters to and from “R” stashed among Olivia’s things, along with a deed to a cottage she owned in Italy. The women also discover Olivia planned to meet R again on her 65th birthday, which would have been a few months away. So they travel to Italy and stay in the cottage, hoping to find R. There, handsome neighbor Hawke catches Dev’s eye and Bailey hits on him, reviving an old feud between the sisters over an ex-boyfriend of Dev’s. Moretti’s depiction of sibling affection and tension is on point, and the plot involving Olivia’s secrets has momentum. This diverting story should still hold readers in its sway. Publishers Weekly, January 2022