BIOGRAPHY

| Brooks, Geraldine | Memorial days |

| Dickson, Peter | He was my brother |

| Ennis, Helen | Max Dupain |

| Shields, Brooke | Brooke Shields is not allowed to get old |

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks

Finding an island for grief. On Memorial Day, 2019, Tony Horwitz, Brooks’ 60-year-old husband, collapsed on a street in Washington, D.C., and died. In the days and months that followed, Brooks found herself hiding behind a “heavy and elaborate” facade, “a fugitive from my own feelings.” Finally, in February 2023, she traveled to a remote island off the coast of her native Australia to allow herself to mourn. In alternating chapters, Brooks creates an absorbing memoir of shocking loss and protracted grief as she reflects on her marriage, her driven, Type A husband, and her future alone. She and Horwitz met at a party when they were graduate students at Columbia Journalism School. A bit shy, she couldn’t help but notice the “tanned, tousle-haired blond in overalls and red sneakers, regaling the small group on the balcony with the woes of living with his brother in Alphabet City,” a rough section of Manhattan. They both went on to successful careers as journalists, including working as foreign correspondents with posts in Cairo, London, and Sydney, where she had hoped they would settle as a family. But Horwitz needed to be in the U.S., preferably within walking distance to a newsstand and coffee shop. After their son was born, when she no longer wanted to go on risky assignments, he encouraged her to try to write fiction. She was in the middle of her novel Horse when he died. Brooks pays homage to the loving, gregarious Horwitz, lashes out at America’s flawed medical system, and deftly conveys the ongoing reverberations of her shattering experience. Like other widowed writers (Joan Didion, Joyce Carol Oates), Brooks both relives the trauma of her husband’s death and keeps his cherished memory alive. A graceful and moving meditation on bereavement. Kirkus Reviews, November 2024.

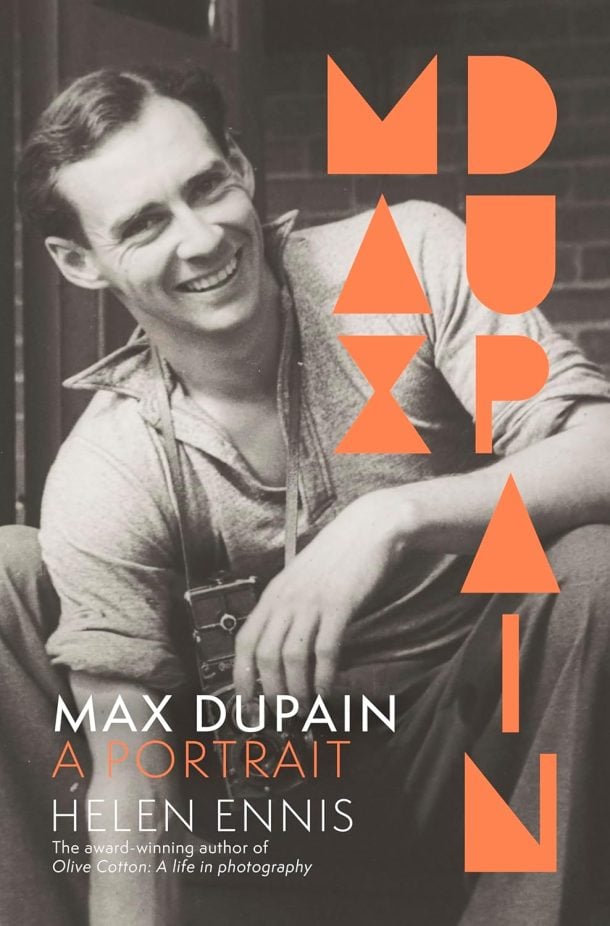

Max Dupain: A Portrait by Helen Ennis

From multi-award-winning writer Helen Ennis comes the first ever biography of the photographer Max Dupain, the most influential Australian photographer of the 20th century and creator of many iconic images that have passed into our national imagination. Max Dupain (1911-1992) was a major cultural figure in Australia, and at the forefront of the visual arts in a career spanning more than fifty years. During this time he produced a number of images now regarded as iconically Australian. He championed modern photography and a distinctive Australian approach. To date, Dupain has been seen mostly in one-dimensional, limited and limiting terms – as exceptional, as super masculine, as an Australian hero. But this landmark biography approaches him as a complex and contradictory figure who, despite the apparent certitude of his photographic style, was filled with self-doubt and anxiety. Dupain was a Romantic and a rationalist and struggled with the intensity of his emotions and reactions. He wanted simplicity in his art and life, but found it difficult to attain. He never wanted to be ordinary. Examining the sources of his creativity – literature, art, music – alongside his approaches to masculinity, love, the body, war, and nature, Max Dupain: A Portrait reveals a driven artist, one whose relationship to his work has been described as ‘ferocious’ and ‘painful to watch’. Australian Arts Review, January 2025.

Return to top>

GENERAL FICTION

| Auster, Paul | Baumgartner |

| Buist, Anne | The oasis |

| Castro, Brian | Chinese postman |

| Cheng, Melanie | The burrow |

| Clark-Platts, Alice | The flower girls |

| Cook, Lorna | The lost memories |

| Erdrich, Louise | The mighty red |

| Erpenbeck, Jenny | Kairos |

| Hickey, Margaret | Rural dreams |

| Hudson, Melanie | The night train to Berlin |

| Isaac-Henry, Olivia | Sorrow spring |

| Mackay, Asia | A serial killer’s guide to marriage |

| McCall Smith, Alexander | The winds from further west |

| Michaels, Anne | Held |

| Morris, Jenny | An ethical guide to murder |

| Moyes, Jojo | We all live here |

| Murakami, Haruki | The city and its uncertain walls |

| Norton, Graham | Frankie |

| Parks, Adele | Just between us |

| Smith, Mark | Three boys gone |

| Trevaldwyn, Harry | The romantic tragedies of a drama king |

| Tyler, Anne | Three days in June |

The Mighty Red by Louise Eldrich

The Mighty Red by Louise Eldrich

The Red River of the North cuts a vivid track through the hardscrabble lives that anchor Erdrich’s surpassing North Dakota fiction. This deft, almost winsome novel begins at night, with Crystal Frechette, a trucker. She’s hauling sugar beets and wearing “a lucky hat knitted by her daughter,” Kismet Poe. Her headlights are “peacefully cutting radiant holes in the blackness” when she glimpses a mountain lion vault across the road. It’s a sign, but of what? Kismet, finishing high school, is edgy, furious, and bored. Both Gary Geist, her school’s quarterback, and Hugo Dumach, a nerdy home-schooler, fixate on her as the angel destined to slay their wildly divergent demons. This nutty love triangle kickstarts the plot; Kismet, in a futile stab at avoiding teen marriage, slips from a bridge into the cold Red River, floating downstream until she’s rescued. But true love here is the kind between mother and daughter. This pair, beset by the 2008 economic meltdown, proves expert in “getting trapped but at least not giving up.” Around them, a recent, communal catastrophe on the frozen river stays murky through three-quarters of the story. In counterpoint, the town’s daffy book club dissects Eat Pray Love and The Road, each session blooming into comic set pieces. Erdrich reaches for some of her fictional staples: a waitressing gig, multiple viewpoints, and, always, mixed-heritage Native people trying to grasp and transmit that heritage. Her writing feels both effortless and wise. She notes a boy’s “shy armpits” and how a soundproofed house can feel “inhuman, maybe even violent.” Even if a minor character, the Catholic priest, bogs down in caricature, Erdrich has few equals in braiding landscape and sky into the marrow of her characters. Her poet’s origins are in full force as she folds in the sickening damage of fracking and pesticide-dependent agriculture, right alongside the sprouts of resistance. In this tender and capacious story, love and tragedy mingle along the river and into the world. Kirkus Reviews, July 2024.

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck

A thorny love affair and a momentous historical moment combine in this novel by prizewinning German playwright and author Erpenbeck, author of Go, Went, Gone (2017), etc. Structured as a series of flashbacks, the novel begins with news of a funeral. Cut to East Berlin in the 1980s and a chance encounter on a public bus. Katharina, 19, meets Hans, a married writer 10 years older than her father. Erpenbeck evokes their early all-consuming passion, fueled by sex and a shared love of music and art, and deftly overlaps their points of view. “Why a love that has to be kept secret can make a person so much happier than one that can be talked about is something she wishes she could understand….Perhaps because a secret is not spent on the present, but keeps its full force for the future? Or is it something to do with the potential for destruction that one suddenly has?” As time passes, rifts and menaces appear. The lovers, from different generations, have experienced different Germanies. “Only a very thin layer of soil is spread over the bones, the ashes of the incinerated victims,” Katharina thinks. “There is no other walking, ever, for a German than over the skulls.” From her apartment in Berlin, she can see the Berlin Wall. Erpenbeck’s handling of characters caught within the mesh (and mess) of history is superb. Threats loom over their love and over their country. Hans is jealous, weak-willed, vindictive, Katharina self-abasing. At heart the book is about cruelty more than passion, about secrets, betrayal, and loss; it’s at its best as the Wall comes down. “Everything is collapsing,” Erpenbeck writes. “The landscape between the old that is being abolished and the new that is yet to be installed is a landscape of ruins.” The personal and the political echo artfully in the last years of the German Democratic Republic. Kirkus Reviews, March 2023.

Held by Anne Michaels

Held by Anne Michaels

Held, the new novel by Anne Michaels, is a haunting meditation on our need to find meaning, to rediscover hope after deep loss, to rationalise the past and shape the future. Michaels’ prose is luminous and crystalline, a reflection of her equally brilliant poetry (she is a former poet laureate of Toronto). Beginning with a First World War battlefield near the River Aisne in 1917, where a soldier lies injured in the snow, the narrative is fragmentary, moving backwards and forwards in time and generations through war and peace and as far into the future as 2025. Against a backdrop of themes such as the development of photography, Marie Curie’s discoveries, the struggle for women’s suffrage, Darwin’s radical ideas, different characters play out their individual lives. Like photography, the focus alternately widens and narrows, sharpening and delineating, softening and broadening, moving between the intricacies of day-to-day existence, and the force fields of history. Like a transformative poem, or a song, it’s a book that needs to be read and re-read to fully absorb the intense inner life of the words on the page. As in real life, there’s a sadness that underscores the ostensibly ordinary lives of the characters but also a sense of exhilaration that life will always transcend death. A question asked by one of the women characters continues to resonate with me, a question that seems particularly topical and one we must go on asking ourselves: ‘Do you think it’s possible … for good to survive long enough to outlast, to wait, to endure, while evil consumes itself?’. Good Reading Magazine, December-January 2024.

We All Lived Here by Jojo Moyes

We All Lived Here by Jojo Moyes

A recently divorced writer juggles a chaotic full house, a struggling career, and a confusing romantic life. Lila Kennedy thought she had the perfect family—a loving mother, a doting stepfather, two wonderful daughters, and a great husband. She even wrote a self-help book about repairing a marriage, which was published a mere two weeks before her husband left her. After her own mother’s sudden death, Lila finds herself an unexpected single mom with her health-nut stepfather, Bill, for a roommate. When her long-absent actor father, Gene, moves in, things go from crowded to chaotic. When Gene isn’t talking about his memories of starring on a Star Trek–like television show, he’s starting fights with Bill. Perhaps the worst part is that Lila’s supposed to produce a new book about the unexpected direction her life has taken. She quickly finds that writing about her real-life romantic exploits (including the kind gardener Bill hired and the sexy single dad she lusts after at school pick-up) and the actual heartbreak that upended her family is easier said than done. Moyes creates a world that is believable and funny. It’s hilarious to read about the distinct characters in Lila’s life—such as her lentil-loving stepfather and egocentric biological father—interacting with each other. There’s plenty of drama here, but none of it feels forced. It all comes from flawed people doing their best to coexist and making plenty of mistakes along the way. Moyes combines the warmth of an Annabel Monaghan rom-com with the humanity of a Catherine Newman novel, creating a story that will provoke tears and laughter. A moving, realistic look at one woman’s post-divorce family life that manages to be both poignant and funny. Kirkus Reviews, November 2024.

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

Three Days in June by Anne Tyler

Their daughter’s wedding stirs up uncomfortable memories for a divorced couple. The day before the ceremony, the bride’s mother, Gail Baines, second in command at the Ashton School in Baltimore, learns that not only has she been passed over to replace the retiring headmistress, but the new recruit is bringing her deputy with her. The lack of people skills that have cost Gail this promotion are evident even in that initial scene; she’s a classic cranky Tyler protagonist, given to blurting out her opinions with little consideration for others’ feelings. Her first-person narration also reveals her to be touchingly vulnerable, convinced that daughter Debbie, prettier and more polished than she, will inevitably prefer husband-to-be Kenneth’s overbearing, better-off parents. Although her divorce from Max was amicable, Gail considers him a bit of a slacker, and isn’t best pleased when he turns up with a rescue cat in tow and says he has to stay with her because Kenneth is horribly allergic. A startling revelation from Debbie, fresh from her pre-wedding “Day of Beauty,” immediately divides the exes, who have very different opinions about how their daughter should handle this crisis. It also leads to Gail’s revelation of the infidelity that led to their divorce, though not in the way readers might imagine. Laid-back Max is the only fully fleshed character here other than Gail, and the novel is very short, but Tyler’s touch is as delicate, her empathy for human beings and all their quirks as evident in her 25th work of fiction as it was in her first, published an astonishing 60 years ago. Gail’s acerbic observations about the wedding and all its participants, her wistful memories of her odd-couple romance with Max, and her account of their enforced intimacy over the three days surrounding the wedding alternate to poignant effect. The closing pages offer a happy ending that feels true to the characters and utterly deserved. Sweet, sharp, and satisfying. Kirkus Reviews, October 2024.

Baumgartner by Paul Auster

Baumgartner by Paul Auster

Auster (The Brooklyn Follies) offers a profound character study of a man whose advancing years are shaped by mourning and memory. Sy Baumgartner is a 70-year-old philosophy professor at Princeton who, at the novel’s outset, has spent the past decade grieving his beloved wife Anna’s death in a swimming accident. Though he attends to a banal domestic routine, writes scholarly books, and even proposes marriage to a divorced colleague, Sy is so surrounded by effects of his old life with Anna (including manuscripts of her poetry, a book of which he shepherded into print posthumously) and so steeped in his reminiscences of her that at one point he becomes convinced she’s called him over a long-ago disconnected phone line to assure him “that the living and the dead are connected, and to be as deeply connected as they were when she was alive can continue even in death.” Sy lives simultaneously in both the present and the past, and Auster navigates these two narrative tracks nimbly: an uncovered box of Anna’s postgraduate papers leads to a reverie about her and Sy’s courtship decades earlier; a present-day moment of absentmindedness conjures recollections of Sy’s multigenerational family. The effect builds to a beautiful approximation of memory’s fluidity and allure. This is one to savor. Publishers Weekly, September 2023.

Return to top

HISTORICAL FICTION

| Williams, Sue | The governor, his wife and his mistress |

Return to top

MYSTERY

| Bowen, Rhys | We three queens |

| Carter, Alan | Prize catch |

| Horst, Jorn Lier | Traitor |

| Jackson, Holly | A good girl’s guide to murder |

| Kellerman, Jonathan | Open season |

| Manansala, Mia P. | Guilt and ginataan |

| Martin, Faith | Murder by candlelight |

| McFadden, Freida | The boyfriend |

| Parkes, Geoff | When the deep dark bush swallows you whole |

| Patterson, James | Holmes is missing |

| Raybourn, Deanna | Killers of a certain age |

| Robb, J. D. | Bonded in death |

| Rubin, Gareth | Holmes and Moriarty |

| Walsh, Bridget | The tumbling girl |

Prize Catch by Alan Carter

Prize Catch by Alan Carter

Alan Carter’s latest crime novel, Prize Catch, is a page-turning thrill ride set on Australia’s Emerald Isle. With the action taking place in Hobart and its surrounds, and brimming with beautiful descriptions of the picturesque, and at times unforgiving, Tasmanian landscape, this thriller focuses on the unlikely alliance formed among Roz Chen, a grieving widow; Sam Willard, an SAS veteran; and Jill Wilkie, a police officer on the verge of retirement, as they find themselves pulled into a murky underworld—with links to salmon farming, environmental activism and allegations of war crimes. The novel races along, unravelling crimes and schemes in rapid succession, until it seems as if the final reveal will happen at the halfway mark and there could not possibly be anything of consequence left to occur. However, Carter expertly unspools another twist in the plot, which propelled this reader through to the end. At times, the extreme lengths the ‘bad guys’ go to, their motives, and the sheer number of times some characters find themselves in perilous and/or near-death situations seem a bit far-fetched, but sometimes personal, political and corporate greed forces people to do things beyond the credible. For fans of Chris Hammer and Garry Disher and readers of Carter’s previous novels, Prize Catch exposes the lengths some people will go to get what they want and the sacrifices others will make to stop them. Publisher’s Weekly, August 2024.

A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder by Holly Jackson

A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder by Holly Jackson

Five years prior to this book’s start, 17-year-old Andie Bell disappeared from the small town of Fairview, Conn. Her body was never found, but her boyfriend, Salil Singh, was blamed for her murder after he texted a confession to his father and died from an apparent suicide. High school senior Pippa Fitz-Amobi remembers how kind Sal was, and she thinks he may have been innocent; via her senior project, she aims to prove it. Though Pip, an adept snoop, is forbidden from contacting the victims’ families, Sal’s younger brother, Ravi, insists on helping, and Pip begins interviewing anyone who might have information about the spring night Andie went missing. Pip assumes they’re on the right track when she starts to receive threatening notes that place her in the crosshairs of someone determined to keep a dark secret. Jackson sprinkles the fast-paced narrative with Pip’s notes, project logs, and interview transcripts—as well as several cleverly placed red herrings— while exploring how the Singh and Bell families suffered in the aftermath of the alleged crime. Jackson caps her suspenseful, well-plotted mystery with a few twists that readers likely won’t see coming. Fans of Veronica Mars and its ilk will find plenty to enjoy in Jackson’s assured debut. Publisher’s Weekly, November 2019.

Killers of a certain age by Deanna Raybourn

Killers of a certain age by Deanna Raybourn

Four female assassins on the brink of retirement are brought back into the game by a surprising assassination attempt—on them. Since they were recruited in their 20s, Billie, Mary Alice, Helen, and Natalie have been working as secret assassins for a clandestine international organization originally created to hunt Nazis. Now they’re in their mid-60s, and the Museum—as its denizens call the elite group—has sent them on an all-expenses-paid cruise to celebrate their retirement. Several hours into the trip, though, Billie discovers another of the Museum’s assassins onboard the ship. It turns out that she and her colleagues have uncovered a plot to end their own lives. They’re forced to flee while simultaneously solving the mystery of why their employers have put targets on their backs. The story jumps back and forth between the late 1970s and early ’80s, when the women were first recruited, to the present day, when the female assassins have all lived long, full lives and worry about menopause and lost spouses more than whom they might kill next. Juxtaposing the two timelines creates an interesting dichotomy that examines the nuances of the female aging process from a unique angle. The writing is witty and original, and the plot is unpredictable; Billie is a complex and likable character, but the other three women, while easy to root for, tend to blend together. As the women race around the world trying to stay alive, Raybourn vividly evokes a number of far-flung locations while keeping readers on their toes trying to figure out what’s going to happen next. A unique examination of womanhood as well as a compelling, complex mystery. Kirkus Reviews, July 2022.

Bonded in Death by J.D. Robb

Bonded in Death by J.D. Robb

Lt. Eve Dallas and her colleagues in the New York Police and Security Department step outside their comfort zone into counterterrorism. Back in 2024, during the stressful time of the Urban Wars, a courageous band calling themselves The Twelve fought Dominion and other violent fringe groups that sought to end civilization as we know it, despite the presence of a traitor in their own midst. Now, 37 years later, someone’s killed Giovanni Rossi, a retired cybersecurity expert who was one of The Twelve, an hour or so after a summons—ostensibly from another veteran of the group—brought him from Rome to New York. On the body, officers called to the scene find a copy of Dallas’ business card that’s been embellished with a flamboyant threat to annihilate the seven surviving members of The Twelve. Obligingly inviting all seven to New York—a move you’d think would make it a lot easier for their nemesis to wipe them all out at once—Dallas soon forms a theory about the killer’s identity and sets a trap to draw him out. But her plan turns into a narrow miss, upping the stakes on both sides, for now the killer knows Dallas is on to him. It’s in the nature of the case that there’s less mystery and detection than usual in this long-running franchise—the biggest surprise turns out to be the connection between Dallas and her quarry—but the thrills keep on coming, and the final interrogation, though highly predictable in its broad outlines, is as satisfying as ever. Forget the tangled backstory, focus on the game of cat and mouse, and enjoy. Kirkus Reviews, November 2024.

Return to top

NON FICTION

| Baker, Eleanor | Book curses |

| Byrne, Bob | Remember when… |

| Fanon, Frantz | The wretched of the Earth |

| Gripper, Ali | Saltwater cure |

| Helmuth, Diana | Hidden libraries |

| Lodge, Sara | The mysterious case of the Victorian female detective |

| McWilliams, David | Money |

| Sobel, Dava | The elements of Marie Curie |

| Valentine, Carla | Murder isn’t easy |

The Elements of Marie Curie by Dava Sobel

The Elements of Marie Curie by Dava Sobel

Admiring biography, by the noted popular historian of science, of the extraordinarily accomplished Madame Curie. As of now, notes Sobel in her opening pages, Marie Curie, née Marya Salomea Slodowska, is “the only Nobel laureate ever decorated in two separate fields of science.” Sobel points to Curie’s brilliance across a range of disciplines, encouraged by her progressive father, a math teacher at a Warsaw high school, who encouraged all his children to enjoy the sciences but also read Dickens aloud to them in English, “translating the text into Polish on the fly.” Fortunately, at least some of the French scientific establishment was just as progressive, with the Sorbonne admitting women into medical school, and there Marya, now Marie, went, changing her study track to physics. That was a hard slog; as Sobel writes, she still had some catch-up work to do in math, and in French, a language not her own. Still, in 1893, two years after arriving in Paris, she came in first in her class and began studying for a doctorate, her topic the relatively unexciting “magnetic properties of dozens of varieties of steel.” Enter Pierre Curie, with whom Marie would have a binding love until his unfortunate death; modest to a fault, he made sure to credit her for her work, even if international organizations too often did not. Indeed, Sobel makes plain that Marie was Pierre’s equal and more, making critically important discoveries at the dawn of our understanding of radioactivity—a term that Marie coined. Moreover, Sobel notes, though known as a martyr of science, dying of radiation poisoning in the form of aplastic anemia, Marie Curie should just as properly be recognized for helping dozens of women advance in the sciences. A lucid, literate biography, celebrating a scientific exemplar who, for all her fame, deserves to be better known. Kirkus Reviews, September 2024.

Murder Isn’t Easy: The Forensics of Agatha Christie by Carla Valentine

Murder Isn’t Easy: The Forensics of Agatha Christie by Carla Valentine

The mind of a writer is a strange place, and a mystery writer’s mind is the strangest of all. How does one use a myriad of tiny intersecting events to construct a plot that will puzzle, entertain, surprise, and ultimately satisfy the reader? Carla Valentine reveals the processes by which that mistress of misdirection, Agatha Christie, used what we now refer to as forensics to lend both credibility and complexity to her famous stories. During the first world war, Christie worked in a hospital dispensary, where she learned to mix medicines from precisely measured and often dangerous ingredients. She was, as her autobiography put it, “surrounded by poisons”. Inspired by the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, it was here that her thoughts turned to detective fiction, and she planned her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, a clever and devious case of murder by strychnine poisoning. Following the success of this novel, Christie decided to go beyond poisons and thoroughly familiarise herself with emerging scientific techniques that were changing the investigation of crime. Valentine has employed her skills as a forensic mortuary technician to tease out the fine details of how Christie wove this knowledge into her stories. Valentine’s book also serves as an exploration of those techniques, including the collection of fingerprints, the interpretation of impressions like footprints or tyre tracks, the analysis of bloodstains and, at the autopsy stage, of the victims themselves. In some areas, notably fingerprints, Christie’s novels, perhaps as a result of her conversations with experts, anticipated innovations before they were formally adopted. Valentine has written an engaging and informative book (the Murder Methods Table is grimly fascinating, with 1939’s And Then There Were None claiming the prize for the greatest diversity, from crushing to drowning). She casts new light on Christie’s methods and research and, most importantly, makes sure never to give away the endings. The Guardian, November 2021.

Return to top

ROMANCE

| George, Louisa | Resisting the single dad next door |

Return to top

SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY

| Corey, James S. A. | The mercy of gods |

| Keetch, Sophie | Morgan is my name |

| Sanderson, Brandon | Rhythm of war |

| Scheurer, Helen | Iron & embers |

| Swan, Richard | The tyranny of faith |

| Talabi, Wole | Shigidi and the brass head of Obalufon |

The Mercy of Gods by James by S.A. Corey

The Mercy of Gods by James by S.A. Corey

The first installment in the pseudonymous Corey’s Captive’s War series begins an epic narrative about a subjugated humankind and its tenuous survival in the midst of an ancient war. When the godlike Carryx—who have “ruled the stars for epochs”—and their minion races arrive around the planet Anjiin, the humans who live there are conquered seemingly without effort. After one-eighth of the population is quickly killed, those worthy of saving are separated and taken off-planet, back to one of the Carryx’s world-palaces. Once there, the remaining humans realize they’ve finally had some important scientific questions answered: “Alien life exists, and they are assholes.” The humans’ predicament is simple: If they’re not beneficial to the Carryx in some way, their entire race will be eliminated. Trapped in a massive prison world with hundreds of other enslaved races, elite researchers like Dafyd Alkhor and Tonner Freis must stay alive long enough to prepare some kind of retribution against their alien overlords. While the character development is exceptional, the pacing breakneck, the emotional intensity off the charts, and the worldbuilding simply extraordinary, it’s the sheer scope of the narrative—the Carryx’s backstory, their “long” war, the countless sentient races they’ve conquered and/or destroyed, etc.—that will have science fiction fans befittingly blown away. The sense of wonder associated with the story’s magnitude is simply breathtaking. Here is just an example of one of the Carryx’s world-palaces: “The huge arcs of alien structure, one part building and two parts the bones of strange gods, glittered with a million other windows like theirs. The ziggurats that marched along the curve of the planet, poking their sullen bronze heads up above the clouds, were a cityscape twisted by nightmare, starkly beautiful but vast enough to induce vertigo.” The beginning of what could be Corey’s most epic—and entertaining—series yet. Simply mind-blowing. Kirkus Reviews, July 2024.

Morgan is My Name by Sophie Keetch

Morgan is My Name by Sophie Keetch

Keetch’s debut adds to the ever-growing subgenre of feminist reimaginings of the lives of villainous women from myth and legend with this balanced take on Camelot’s Morgan le Fay. Named Morgan (or “sea-born,” in Welsh) after the sea that her mother, Lady Igraine, claims helped bring Morgan into the world, she and her two older sisters grow up happy at Tintagel—until their father dies. Lady Igraine is compelled to remarry King Uther, and from there Morgan’s life takes a turn for the worse, though she still ekes out moments of happiness in an affair with a squire. When her transgressions are discovered, she is banished to a nunnery, but Igraine ensures that she receive a decent education, and Morgan’s increasing knowledge of the healing arts sets her on a path toward magic. As Morgan’s power grows, so too does her desire for freedom and independence, pitting her against the men who try to control her. With equal attention to politics and witchcraft, Keetch’s exploration of Morgan’s growth shows how the perspective of men has warped the character over the years. Fans of Arthurian legends retold will not want to miss this. Publisher’s Weekly, April 2023.

The Tyranny of Faith by Richard Swan

The Tyranny of Faith by Richard Swan

This grimdark political fantasy thriller is the second of a trilogy chronicling the fall of an empire. Imperial Justice Sir Konrad Vonvalt; his clerk (and the novel’s narrator), Helena Sedanka; and their two companions have traveled to Sova, capital of the Empire of the Wolf. There they intend to confront the traitorous Justices of the Magistratum, who have been sharing their secret magical knowledge with zealous priest Patria Bartholomew Claver, and gain the emperor’s assistance in going after Claver, who is currently raising an army and may have designs on the throne. But their efforts are stymied by the suspiciously timed kidnapping of the Emperor’s grandson, which Sir Konrad is ordered to investigate, and the debilitating illness afflicting Sir Konrad, the result of a hex cast by Claver. As Sir Konrad and his compatriots seek to solve a mystery, discover a cure, and find allies against Claver in an increasingly complex and treacherous political landscape, Helena battles both her feelings for Sir Konrad and her repugnance for some of his recent ruthless actions, which suggest that he is more and more willing to ignore the letter of the law in his pursuit of both justice and vengeance. While the previous installment, The Justice of Kings (2022), was pretty dark, this volume gets even grittier, as the remaining scraps of Helena’s naïveté about Sir Konrad’s character and the nature of his work are brutally burned away and any faint hope that law might win out against might and self-serving politicking is crushed out in a fairly definitive way. It is now obvious that this empire of fractious, recently conquered nations is beyond saving, and all the characters can do is fight toward preserving whatever safety they can. This book travels even further beyond the traveling investigator/justice dealer mold of Tremayne’s Sister Fidelma and van Gulik’s Judge Dee series and more squarely into territory reminiscent of Andrzej Sapkowksi’s Hussite trilogy, another complex and dark historical fantasy series inspired by medieval state-military-church political conflicts. Doom is inevitable; it will be interesting (and no doubt, heart-wrenching) to see what form it will take. Kirkus Reviews, November 2022.

Shigidi and the Brass Head of Obalufon by Wole Talabi

Shigidi and the Brass Head of Obalufon by Wole Talabi

This frenetic fantasy debut from Nigerian author Talabi starts out noir, with a car chase across the “spirit-side” of London while antihero Shigidi bleeds out in the back seat of a cab. Then the shenanigans really ramp up, flashing back to how Shigidi wound up there. The ensuing romp is a heist caper with sex, violence, and superpowers popping off every Technicolor page. Shigidi, former Nigerian nightmare deity, slips the daily grind of the Orisha Spirit Company for the persuasive tutelage of freelance succubus Nneoma, who’s training him to become a succubus himself. But freedom has its price, and when the big god Olorun calls in a favor, Shigidi and Nneoma have mere hours to lift an ancient Nigerian talisman from the British Museum and escape the retributive justice of the Royal British Spirit Bureau. Readers of Neil Gaiman and Harry Turtledove will have encountered similar takes on the spirit realm; Talabi’s freshness is in his language, his caustically amusing protagonist (Shigidi describes a supernatural effusion as “light gushing out… like a vandalized pipeline”), and his commitment to having more fun than noir usually allows. Readers are in for a rollicking thrill ride. Publisher’s Weekly, October 2023.

Return to top

New additions to eBooks at SMSA

EBOOKS

| General | Kang, Han | Greek lessons |

| General | Llewellyn, Caro | Love unedited |

| General | Ryan, Madeleine | The knowing |

| General | Taylor, C. L. | Every move you make |

| General | Woods, Evie | The story collector |

| Gneral Fiction | Baxter, Ella | Woo woo |

| Historical | Dunn, Kat | Hungerstone |

| Mystery | Sandler, Rosie | Seeds of murder |

| Mystery | Edwards, Martin | Gallows court |

| Mystery | Osler, Rob | The case of the missing maid |

Greek Lessons by Han Kang

Booker winner Kang (The Vegetarian) explores the borders of the senses in this delicate love story. An unnamed Korean woman living in Seoul stops speaking after her mother dies and she loses custody of her eight-year-old son. An interest in language, though, continues to tug at her, and she enrolls in a Greek class. There, she begins writing poetry that catches the eye of her instructor who, unbeknownst to anyone else, is slowly losing his sight. Split between his dual homelands of Korea and Germany, the instructor picks up on the student’s search for a language beyond what can be expressed or seen with the naked eye, something the woman gestures at in her poetry: “a language as cold and hard as a pillar of ice.” In prose that merges memory, story, and poetry, Kang tracks how the two find in one another what is missing from the sensual world. This brilliant, shimmering work is never at a loss for words even when exploring the mind of a woman who won’t speak, and its pursuit of an authentic, exquisite new form is profound. Once again, Kang demonstrates great visionary power. Publishers Weekly, February 2023

Love Unedited by Caro Llewellyn

Reading Caro Llewellyn’s debut novel, Love Unedited, is like reading someone’s diary entries on life and love, which is fitting for this story within a story. Set predominantly in New York City and the publishing world, the novel introduces Australian editor Edna, who finds herself drawn to an acclaimed writer. The pair have an indisputable connection and over the decades find themselves falling in and out of each other’s lives. Alongside this narrative is Molly’s story. Molly is also an Australian editor working in New York and is consumed by the search for the anonymous author of a manuscript she can’t stop thinking about. A unique blend of literary fiction, metafiction and romance, Love Unedited is a character-based novel that explores the minutiae of love and relationships in intimate and compelling detail. The meandering narrative feels genuine and nostalgic, allowing the reader to truly connect with the characters. This authenticity is further enhanced by narrative threads that include discussions around diseases and disability, commentary on the publishing industry, and some deliciously rich accounts of restaurants and food. Celebrating life’s highs and lows, this multi-layered novel is an ode to love in its various forms and is recommended for readers who enjoyed Llewellyn’s Stella Prize-shortlisted memoir, Diving into Glass, David Levithan’s The Lover’s Dictionary and Heather Rose’s The Museum of Modern Love. Publisher’s Weekly, January 2025

The Knowing by Madeleine Ryan

The Knowing by Madeleine Ryan

Camille works for a semi-famous florist in Armadale, where she commutes daily from her home in the country. She yearns for a life full of beauty and meaning and can’t understand why, despite her efforts, she is unhappy. Like Madeleine Ryan’s first novel, A Room Called Earth, The Knowing unfolds across a single day in the close third-person perspective, giving the reader an intimate window into Camille’s thoughts, memories, hopes, dreams and fears. On this day, Camille forgets her phone and faces her long commute without the comfort of distraction. On her journey, she contemplates how she betrays herself to please those around her, whether it be her boyfriend, Manny; her toxic boss, Holly; or her family. Millennial Camille, with her phone-obsessed and idealistic nature, will be a character many will relate to, though her true depth emerges more through the eyes of other characters than through her own actions and opinions. The vignette-style chapters address timely topics such as capitalism, feminism, burnout, addiction, work culture, relationships and women’s bodily autonomy. Much like Camille, these ideas are rich with potential; the book would benefit from deeper exploration of both. Still, Camille offers an authentic portrayal of the inner conflict many women face when self-doubt clouds their path and they downplay their talents out of uncertainty and insecurity. The Knowing will resonate with readers of autofiction and those who enjoyed Ryan’s debut, offering a thought-provoking exploration of self-discovery and the complexities of modern life. Publisher’s Weekly, January 2025

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter

Woo Woo by Ella Baxter

In Woo Woo, Ella Baxter’s raucous second novel after New Animal, art is terrible, a living spell, a parasite, a trick, and all there is. ‘Art is life,’ writes protagonist Sabine on her socials bio. ‘No babe, we’ve been through this,’ says Sabine’s friend Ruth, ‘art is art’. It’s the week before Sabine’s exhibition, Fuck You, Help Me, at Goethe—which boasts the second-biggest advertising budget in the gallery’s history—and Sabine keeps acting stranger. Sabine makes human-sized puppets (‘gothic skins’) and photographs her nude self wearing them. Her husband, Constantine, swears he ages twenty years in the week leading up to her showings. ‘Imagine what it’s like for me,’ says Sabine. Between bouts of sleeplessness, neediness, gorging, obsession, chugging, and spontaneous live streaming, Sabine is stalked by the increasingly ominous Rembrandt Man and consoled by the ghost of artist Carolee Schneemann. In ripe-to-fetid and deliciously droll prose, Baxter ponders what shapes our fury, our fear and our selfhood might take in the wake of men’s violence, turbo-capitalism and being extremely online, and makes a titillating case for going feral, committing fully to the bit, and haunting our enemies forever. Woo Woo is a spooky, darkly combustible feast for fans of Sally Olds’s People Who Lunch, Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle’s Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life, Ania Walwicz, Miranda July, Melissa Broder and Dorothea Lasky, and anyone who’s ever wanted to run naked into a forest, screaming. Publisher’s Weekly, June 2024

Hungerstone by Kat Dunn

Hungerstone by Kat Dunn

Dunn (Dangerous Remedy) offers a moody and triumphant retelling of Carmilla, the 1872 gothic novella by Sheridan Le Fanu, about a married woman in Victorian London who experiences an existential and sexual awakening at the hands of a female vampire. Lenore Crowther, 30, a restless aristocrat, sleeps alone in the drafty mansion she shares with Henry, a steel mill magnate, whom she married for his money. When the couple witnesses a roadside carriage accident, they rescue the distraught victim, Carmilla Kernstein. As Carmilla recovers, Lenore realizes how much their new guest resembles a ghostly girl who’s been haunting her dreams. Soon, Carmilla kindles a long-buried desire in Lenore and turns Lenore into a vampire like herself. Bodice-ripping and bloodsucking ensue, as Lenore discovers her independence. Dunn portrays the newly awakened Lenore as increasingly outspoken, empowered, and fearless, turning the novel into a meditation on womanhood, corporate greed, and queer desire, delivered in frank prose (“To be a woman is a horror I can little comprehend”). This revitalizes Le Fanu’s classic tale without losing any of its appeal. Publisher’s Weekly, December 2024

Gallows Court by Martin Edwards

Gallows Court by Martin Edwards

In this exceptional series launch from Edgar–winner Edwards (Dancing for the Hangman) set in 1930 London, ambitious tabloid journalist Jacob Flint is hoping to make a name for himself by interviewing Rachel Savernake, a judge’s daughter, whose amateur detecting solved a murder that baffled Scotland Yard. Rachel had identified Claude Linacre, a prominent politician’s brother, as the killer shortly before Linacre fatally poisoned himself. After Rachel rebuffs Jacob’s inquiries about the Linacre case, she persuades a terminally ill banker and philanthropist to write a confession that he strangled and dismembered a nurse—and then shoot himself. Entries from an 11-year-old journal, written by someone whose role is initially unclear, accuse Rachel of being a murderer. More bloodshed follows as Jacob tries to figure out Rachel’s motives and culpability. The labyrinthine plot is one of Edwards’s best, and he does a masterly job of maintaining suspense, besides getting the reader to invest in the fate of the two main characters. Fans of Edgar Wallace’s classic Four Just Men won’t want to miss this one. Publisher”s Weekly, July 2019

The Case of the Missing Maid by Rob Osler

The Case of the Missing Maid by Rob Osler

The first woman hired by a Chicago detective agency faces one daunting challenge after another in this excellent historical series launch from Osler (Cirque du Slay). When Harriet Morrow reports for her first day at the Prescott Detective Agency in 1898, she’s determined to make a success of it and leave her dull bookkeeping career behind. Yet from the minute Harriet walks through the door, she’s met with skepticism from her male colleagues. Only the boss, Theodore Prescott, believes in her, but even he gives her an apparently toothless assignment: report to the home of Pearl Bartlett, an elderly and often confused widow, to follow up on her complaint that her maid, Agnes Wozniak, has disappeared. While Pearl has a reputation for crying wolf, Harriet believes her this time and suspects that Agnes has been abducted. As Harriet digs deeper into the case, she also grapples with escalating hostility at the detective agency, wariness among Agnes’s peers in Chicago’s Polish community, and fears that her secret life as a lesbian might be exposed and used against her. As the intrepid, bike-riding lady detective plunges into Chicago’s seedy gay clubs and criminal hangouts, Osler doles out well-placed clues that set the table for a knockout conclusion. With lush historical detail, optimistic but plausible gender politics, and an unforgettable heroine, this series is primed for success. Publisher’s Weekly, November 2024

Return to top

AUDIOBOOKS

| Biography | Osborne-Crowley, Lucia | The lasting harm |

| General | De Kretser, Michelle | Theory & practice |

| General | Stephens, Mary-Lou | The jam maker |

| Mystery | Hardy, Fiona | Unbury the dead |

| Mystery | March, Nev | Murder in old Bombay |

| Mystery | McDonnell, Caimh | A man with one of those faces |

| Mystery | Prak, Michelle | The rush |

| Mystery | Archer, C. J. | The convent’s secret |

| Romance | Everett, Elizabeth | The love remedy |

| Sci-Fi/Fantasy | Beaglehole, Iris | Accidental magic |

The Lasting Harm by Lucia Osborne-Crowley

The Lasting Harm by Lucia Osborne-Crowley

It’s not often a book reverberates around my head for days. But there is something brilliantly unsettling about this account of the trial of Ghislaine Maxwell, the British socialite jailed for procuring young girls for the billionaire paedophile Jeffrey Epstein. Having watched from the press box as the case descended into a media circus, Lucia Osborne-Crowley begins by promising to put the victims back at the heart of the story, tracing the impact of the abuse they suffered as children through to their middle-aged lives. But it soon emerges that this book isn’t just about the vulnerable teenagers Maxwell and Epstein groomed for sexual entertainment, exploiting their desperation for affection or for money. It’s also about the author and, less comfortably, the reader too. A paralegal turned freelance journalist, Osborne-Crowley was abused herself from the age of nine by a non-family member, then violently raped at 15 by a stranger (something she has written about extensively in two previous books). She makes no pretence at journalistic distance from her subject, but instead a virtue out of being almost too close to it: less objective narrator than increasingly traumatised participant. At first, I find her habit of constantly inserting herself into a story supposedly centring other victims faintly irritating. By the end, I’m converted. By interweaving her own insights with those of the Maxwell victims she interviews, she forms the bigger picture. Where the book excels however is in its empathy, insight and ability to gently expose the reader to themselves, with all their unthinking assumptions. Osborne-Crowley wasn’t, it turns out, just watching the trial. She has been watching us, watching it, through a lens that most don’t even realise is there. The Guardian, July 2024

Theory & Practice by Michelle de Kretser

Theory & Practice by Michelle de Kretser

In this sharp-witted and mesmerizing outing from de Kretser (The Life to Come), a Melbourne graduate student navigates the disconnect between her feminist ideals and her messy love life. The unnamed narrator, who’s writing a thesis about the portrayal of gender in Virginia Woolf’s novels, recounts her childhood in Sri Lanka, where she was sexually abused by a British man at 11. She went on to embrace feminism, and she struggles now with French post-structuralist theory, which is in vogue on the Melbourne campus, because of its indifference to feminist issues and her desire to upend the patriarchy (“One could not overthrow the Father, who was always already dead, although his phallus was everywhere in society and culture”). She also ruminates on contemporary Australian films, such as Gillian Leahy’s Life Without Steve, which follows a woman over one year as she attempts to move on from an affair. The film resonates with the narrator because of her own tortured love affair with a fellow student who remains committed to his girlfriend (“I thought, I didn’t know that this could be art. It was the first time I’d seen my everyday, unglamorous world in a film”). The narrator also vacillates between prizing intellectual theorizing or direct action, reflecting on the anticolonial resistance of Ceylonese activist E.W. Perera. Taken together, the narrator’s clever political insights and beautiful depictions of art and literature offer readers a view into a captivating mind. De Kretser is at the top of her game. Publisher’s Weekly, October 2024

Unbury the Dead by Fiona Hardy

Unbury the Dead by Fiona Hardy

Fiona Hardy’s Unbury the Dead is a masterful blend of fast-paced crime and Australian noir, balancing grit and dry humour with effortless skill. Set against the vivid backdrops of rural and suburban Victoria, this crime thriller introduces two heroines – Alice and Teddy – and their warm and authentic friendship. Hardy’s knack for crafting sharp, natural dialogue shines throughout, making even the darkest moments crackle with life. Alice and Teddy work for Choker, a man running a morally ambiguous operation. Alice is hired for a seemingly quick job for good pay – to drive a dead billionaire home to his resting place before anyone realises he is gone. Meanwhile, Teddy is tasked with finding a missing teenager no one seems to care about. The chapters alternate between Alice and Teddy as their parallel experiences reveal some great plot twists. Hardy excels in creating tension, particularly through the layered motivations of her lead characters and their morally complex decisions. The dynamic between Alice and Teddy anchors the novel, while the well-drawn supporting characters – Choker, Art, and Rusty – provide counterpoints of humour and emotional richness. For fans of Peter Temple’s Jack Irish novels or Mick Herron’s Slough House series, Unbury the Dead is a terrific read that marks an impressive adult debut for Hardy. Publisher’s Weekly, February 2025

Murder in Old Bombay by Nev March

Murder in Old Bombay by Nev March

Set in 1892 Bombay, March’s assured debut stars Jim Agnihotri, an Anglo-Indian army captain recuperating from an injury suffered on the frontier in Karachi. With little to distract him, he focuses on the sensational deaths of 19-year-old Bacha and 16-year-old Pilloo, members of a prominent Parsee family, who fell from a university clock tower. Rumors swirl that the pair committed suicide, but Agnihotri sees too many contradictions in reports about the deaths to believe it. When he reads an anguished letter-to-the-editor in The Chronicle of India from Bacha’s husband, he becomes determined to find out why Bacha and Pillo died. A friend also gives Agnihotri a copy of Conan Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes novel, The Sign of the Four, from which he often draws inspiration. March fills the story with finely developed characters, particularly Agnihotri, who proves a zealous investigator. She also presents an authentic view of India under British rule while exploring the challenges faced by a character of mixed race. The heartfelt ending leaves plenty of room for a sequel. Readers won’t be surprised this won the Minotaur Books/Mystery Writers of America First Crime Novel Award. Publisher’s Weekly, August 2020

The Rush by Michelle Prak

The Rush by Michelle Prak

The Rush by Michelle Prak gives new meaning to the words gripping and horrifying. Take Jane Harper’s The Lost Man, add some sinister Wolf Creek, and you’re on the right (or very wrong) rural noir track. The Rush begins with local Quinn’s discovery of an abandoned body on an isolated road in remote South Australia. Add an agitated group of four backpackers on their way to Darwin, their overlap at the remote outback pub where Quinn works and lives—and let the fun/horror begin. In some ways The Rush is a misleading read. It starts off a bit predictably, as a familiar road-tripping, Gen Z story set in a standard Australian outback setting. While the writing is taut from the beginning, with strong scene-setting and dialogue, you are not prepared for the fast-paced twists ahead. It is anything but your typical outback thriller. The unravelling horror is set up so masterfully by the stream of banal travel banter, ominous weather and testy human dynamics. The characters are developed steadily, evoking physical responses from the reader (the main villain Joost with his ‘pale eyes and hungry sneer,’ a stand-out). Aside from its entertainment value, The Rush makes you think, raising relevant themes of climate change, toxic masculinity and the troubling culture of online gaming communities. The Rush is a strong addition to a popular niche in the reading market—well written, compulsive crime thrillers that transport readers to places they are only brave enough to visit from the safety of their armchairs. Publisher’s Weekly, March 2023

The Love Remedy by Elizabeth Everett

The Love Remedy by Elizabeth Everett

Everett (A Love by Design) delights in her sharp and subversive Damsels of Discovery series launch. At 27, Lucinda Peterson is one of the only female apothecaries in 1843 London, having assumed responsibility for the shop her grandfather and father built, as well as for her two younger siblings and all of the less fortunate who fall ill in the city’s East End. After she puts her trust in the wrong man and he steals her revolutionary formula for sore throat drops, she’s at a loss. Desperate to recover at least some of the credit—and get revenge on her former beau—she hires an agent from Tierney & Co., which offers discreet private investigation services. Enter Jonathan Thorne, 32, a father of one, former prizefighter, recovering alcoholic, and estranged third son of a baron. When another of Lucinda’s formulas goes missing, Jonathan is drawn deeper into her secret world of women scientists fighting misogynists and providing reproductive healthcare when no one else will. Though he has sworn never to fall in love again after the death of his mistress, the more he gets to know brilliant, bighearted Lucinda, the more he can’t resist her. With sharp wit and a keen eye for matters of social justice, Everett brings the period to life while making clear just how far women’s rights have come—and how far they have left to go. This frank, flirty outing will have readers hooked. Publisher’s Weekly, January 2024